Is it possible to have a country without a king?

In the 17th century, it seemed impossible. Every country had a king. So the Dutch had a problem on their hands after they declared themselves independent from the king of Spain in 1581. They offered kingship to the king of France, Henri III, but despite many flowery phrases about eternal friendship between the Dutch and the French, nothing came of it. Then the Dutch regents sailed to London to offer their country as a kingdom to queen Elizabeth I. A treaty was drafted, and although she didn’t become sovereign herself, her favorite Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester became sovereign in her stead. There was no chemistry between him and the Dutch thus, by necessity, after he returned to England, the Netherlands became a republic. For the rest of Europe, this was crazy: a country with no king, governed by parliament; who had ever heard of that?

Kingless, the Dutch Republic turned out to be very successful.

The main source of Dutch success was commerce. Amsterdam became the financial and economic center of the world. Famously, the world’s first joint-stock company was founded there in 1603. In search of trade, Dutch ships sailed the oceans. To protect their ships and to keep the seas safe and open, the Dutch employed a Navy. At its apogee, the total of Dutch ships, civilian and military numbered around 2000 (one ship per 750 inhabitants!). Thus the Republic of the Seven Provinces of the Netherlands became master of the Seven Seas.

Many an ambitious and talented young man went out to sea. This was a high-risk/high-reward proposition: some became rich and famous, many died trying.

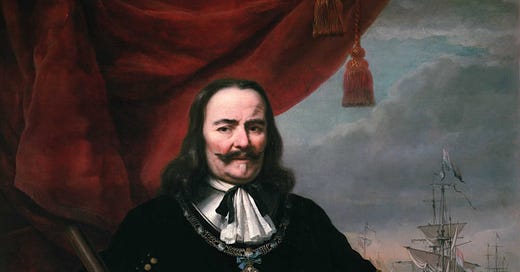

The self-made man who towered over them all was Michiel de Ruyter. Born in Vlissingen (Flushing), he started working in a rope factory at the tender age of seven.

At eleven, Michiel enlisted on a commercial vessel as an apprentice sailor. Many adventures ensued, for example there was the time butter got him out of danger. His ship was pursued by a French pirate, and when the pirates were about to jump over he poured a load of butter on the deck. The enemy sailors couldn’t stay upright and were easily defeated. A slippery slope indeed. In another adventure he was captured by the Spanish and escaped from the prison of La Coruna and with a few comrades walked all 2000 kilometers back to Holland.

Those were the days…

In the following years, he rose through the ranks, becoming helmsman, captain, and then owner of his own merchant ship. On land, he was a cannoneer for three years, fighting with the Prince of Orange against the Spanish. He retired at the ripe old age of 44. Possessing the perfect curriculum, within a year of retirement, he was asked to join the Navy to become a squadron commander, subsequently vice-admiral and ultimately admiral of the Dutch fleet.

In the Baltic, the North Sea, the Atlantic, the Caribbean, and the Mediterranean he fought the Spanish, the French and the Swedish. But his most worthy adversaries were the English.

In the 17th century, there were 3 Anglo-Dutch wars. The wars ended in a draw, but de Ruijter won many great victories. Especially impressive were the battles in 1672 against the combined fleets of England and France.

His most famous exploit though, happened in 1667, conveniently all but forgotten by the English.

In a surprise attack, de Ruijter sailed up the Thames, burned some ships, and scared the shit out of the Londoners, who feared the monarchy might fall and their city invaded. Samuel Pepys contemplated fleeing the capital. Then in a surprise attack, reminiscent of Pearl Harbor, de Ruijter sailed up the river Medway to the harbor of the English fleet at Chatham. The Dutch broke the chain that protected the port and burned down most of the English war fleet anchored there. Then de Ruijter towed the biggest English ship, HMS Royal Charles, back to Holland.

As Samuel Pepys wrote in his diary on the day of the attack, 12 June 1667: “(…) ill news is come to Court of the Dutch breaking the chain at Chatham ; which struck me to the heart. And to Whitehall (the king’s palace) to hear the truth of it ; and there, going up the stairs, I did hear some lackeys speaking of sad news come to Court, saying, there is hardly anybody in the Court but do look as if he cried.”

”Thus in all things, in wisdom, courage, force, knowledge of our own streams, and success, the Dutch have the best of us, and do end the war with victory on their side.”

Those were not just acts of derring-doo but were meant to force the English to the negotiation table and extract favorable terms.

Unfortunately, the HMS Royal Charles was too big to be usable and had to be destroyed. Only its coat of arms remains and can be seen in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam to this day.

Why was de Ruijter (and the Dutch Navy in general) so successful?

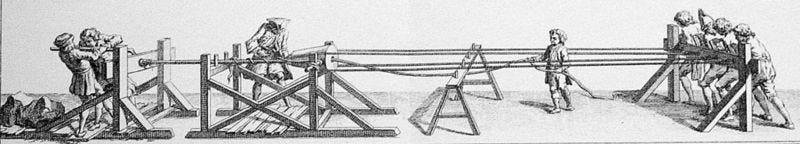

As you would notice when bicycling there, in the Zaan, the region north of Amsterdam, it is always windy. Taking advantage of this, in the 17th century the region was teeming with windmills. You can still see quite a few of them today, just go to Zaandam train station and follow the trail of Japanese and Chinese tourists and you will get here with no problem. Many hundreds of windmills powered all kinds of industries, the most important one sawing lumber. Because the windmills could saw trees into planks so fast, the Dutch were able to build their ships in a shorter time than their opponents and could replace sunk or captured ships faster.

The Dutch navy was a meritocracy, you were promoted because of your capabilities. In the English and French fleets, admirals and commanders were aristocrats. De Ruijter and most of his fellow commanders had been common sailors and rose through the ranks because of their skills and intimate knowledge of all aspects of sailing.

Maybe because of the humble origins of their commanders, Dutch sailors were better paid and thus more motivated to fight. Many an English sailor defected to the Dutch because they paid well and on time. Often the English Navy was months behind in paying, sometimes even years. Not good for morale.

A culture of equality reigned. An English visitor wrote in astonishment how de Ruijter, Europe’s most famous admiral, was sweeping the floor of his own cabin, an unthinkable thing in other Navies. His men even called De Ruijter affectionately grandfather.1

In the Republic, decisions, both on land and at sea, were largely based on consensus (see my explanation of the Polder model here). Although this took more time, often better decisions were reached.

Thus it was proven to the people of the 17th century:

No one needs a king, for a Republic could withstand three kings.

Some of my other pieces on Dutch history and culture:

Bestevaêr in 17th century Dutch.