It is a truth universally acknowledged, that modern architecture is ugly. The only ones to disagree are architects.

Or do they?

Like any normal person, students that start in Architecture school prefer traditional architecture. Only after they have been thoroughly indoctrinated, they begin to prefer modern architecture.

Or do they?

Interestingly, when these students become architects, most ot them live and work in traditional buildings1, not in the kind of buildings they design for other people. Makes you wonder…

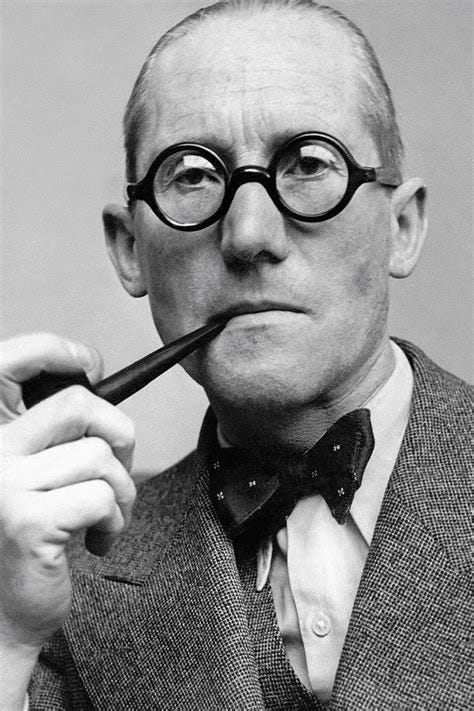

How did this sorry state of affairs come about? One of the ways to answer this question is by looking at the careers of famous architects responsible for all this bad architecture. Therefore, let’s dive into the life of the most influentual of them all: Le Corbusier.

He is one of the patron saints of modern architecture. A Swiss/French architect and city planner (1887-1965), he was a fan of totalitarian dictators like Hitler and Stalin. This is not accidental: in the same way that they wanted to destroy society and create a better utopian one, Le Corbusier wanted to destroy cities to create better ones and thus create utopia.

In 1928 he went to the Soviet Union to talk to Soviet architects and city planners, give lessons and design apartment buildings near the Kremlin.

In August 1940, just after Hitler had conquered France, Le Corbusier wrote to his mother: "Money, the Jews (partly responsible), Freemasonry, everything will undergo the just law". In October, he adds: "Hitler can crown his life with a grandiose work: the development of Europe."

That Le Corbusier liked Hitler and Stalin makes sense. He wanted to destroy the old and create a new world according to a vision of the perfect society, just like Hitler and Stalin did. He believed his buildings would create a new Man, just like Stalin and Hitler believed of their totalitarian ideologies.

Le Corbusier took the word “destroy” literally. For his plan La Ville Radieuse, he wanted to raze Paris and replace it with a landscape full of high rises. Luckily, Paris escaped this madman. A few years later, another madman wanted to destroy the city. In 1944, Hitler had given orders to blow up Paris in case the Allies would take it. Museums, bridges and monuments were wired with explosives. No one knows why General Dietrich von Choltitz, the German military governor of Occupied Paris, decided not to blow up the city, but he didn’t. Isn’t it fair to say Le Corbusier is the Hitler of architecture?

Le Corbusier’s ideas were realized elsewhere, though. They inspired neighbourhoods like The Bijlmer in Amsterdam, the banlieues on the outskirts of Paris, or the Projects all over the US. All of them were disasters: dysfunctional hell holes full of crime, despair and loneliness. So much so that many were destroyed within 40 years of construction because they were unfit for humans.

Le Corbusier is part of an architectual philosophy represented by other venerated architects like Mies von Rohe and Walter Gropius. This philosophy in turn is embedded in the idea that central planning is the way to go: in architecture, in the economy and, untimately, in every aspect of life. This idea was prevalent through much of the 20th century.

Modernist architecture not only disregards the preferences of regular people but also disregards place and climate. A textbook example is Chandigarh. This is the city Le Corbusier designed to be the capital of the states of Punjab and Harya in northern India. In a subtropical climate where summer temperatures can soar to 45 °C, the city has giant plazas and wide avenues providing no shade to its inhabitants. Like the ruins of some ancient civilization, a big part of the city is covered in jungle, 50 years after its construction The vast squares and giant thoroughfares are empty. Concrete has been crumbling for a long time. From dust to dust. Still, it became a Unesco World Heritage Site in 2016.

How is it possible that Le Corbusier is still venerated today?

He is not the only nefarious influence on how much of the modern world was built. One of the other founding fathers of modernism is Walter Gropius. He founded the Bauhaus, the school of design that was the cradle of modernism. From the thirties onwards, he promoted his vision of worker housing - thirteen-story machines for living, as he called them. As all good totalitarians (such as BLM) do, he wanted to abolish the family. Therefore he designed communal spaces, for instance giant cafeterias where people would eat communally, instead of in the privacy of their own homes.

Much of Gropius’s vision got implemented in Communist countries after World War II. In July of 1933, Gropius was in the Soviet Union, railing against “the immoral right of private property”: “Without the liberation of the land out of this private slavery, it is impossible to create a healthy, development-capable urban renewal that is economic in terms of society in general. Only the Soviet Union has fulfilled this most important requirement without reservation, and thereby opened the way for a truly modern urban planning.”

Four years after he made this speech, Gropius was chairman of the architecture department at Harvard, the most prestigious University in the United States. No talk about the immorality of private property anymore. Instead, he spoke about: “Our belief in democratic government blablabla.”

The influence of those men is one reason modern architecture is terrible.

But there is another reason.

For more than 100 years, the hallmark of great art has been that ordinary people dislike it, are puzzled or outraged by it. Thus, if regular people like your art, there must be something wrong with it. The more outrage it generates, the better art is supposed to be. Only intellectuals can appreciate modern art; the plebs are too dumb. Otherwise put: appreciating modern art signals sophistication and high status.

Instead of builders or craftsmen, architects today want to be artists.

That’s why they design ugly buildings.

An example: one of the famest architects of today, Rem Koolhaas, designs buildings similar to the one on the right. He lives in a house like the one on the left, though.

In this interview, Koolhaas first tries to evade the question where he lives. Then he tries to justify the discrepancy between his personal preferences and the buildings he designs for others with a convoluted answer full of impressive sounding phrases:

Hee Henk. Je hebt een vlotte heldere pen. Lekker stellig! Nieuwe kleren van de keizer idee, die studenten van de opleiding voor Architecture. Groet Sanne